The history of Father Joseph J. Ferrara

It all started in 1939 when Rev. Joseph J. Ferrara arrived for his first assignment as a newly ordained priest at Most Precious Blood Roman Catholic Church in Hazleton, Pennsylvania. The pastor, Monsignor Molino, for whom he would now serve as an assistant, wasted no time in delivering the new assistant’s mandate. Ferrara’s reputation as a musician had preceded him and in the presence of a large parish with a lot of children, the directive was simply this: "Start some kind of music program that will keep the kids off the streets and out of trouble."

And so he began the pilot program that he would use throughout the next 60 years of his life. The program was ingeniously simple. He started youngsters in music as early as he could—third grade was a popular age level. In the earliest stage of the program he taught the elements of music such as note recognition and subdivision. He worked relentlessly on key signatures, clefs and counting. To enable practical application, he introduced the incipient musicians to the "Tonette". This was a simple, end-blown flute-like instrument that was extremely easy to master. Once the students had mastered the instrument, they could readily apply all the theory they were absorbing. 12 to 18 months of consistent lessons and diligent practice were usually all it took for the budding musicians to be able to read through all the hand written exercises Ferrara could throw at them.

Beyond this point things became dramatically easier. Only now was it time for a student to pick his or her instrument of choice. Once the decision was made, the learning process began again. This time, however, the process was fueled by the students’ already firm grasp on the fundamentals of music. In almost no time the students acclimated themselves to the instruments they had chosen and, from that time onward, the progress was almost palpable.

Since music "practice" was the single most important after-school activity, it only took but a few years before MPB could boast of a full symphonic band comprised totally of parish youth. Perhaps one of the brightest jewels in the crown of the program was the recital the group played in New York’s famed Carnegie Hall. In 1951, eleven years after receiving his initial mandate, Ferrara was given a new assignment in the Diocese of Scranton’s northernmost sector. Needless to say, what he had built at MPB quickly disintegrated.

Since music "practice" was the single most important after-school activity, it only took but a few years before MPB could boast of a full symphonic band comprised totally of parish youth. Perhaps one of the brightest jewels in the crown of the program was the recital the group played in New York’s famed Carnegie Hall. In 1951, eleven years after receiving his initial mandate, Ferrara was given a new assignment in the Diocese of Scranton’s northernmost sector. Needless to say, what he had built at MPB quickly disintegrated.

After approximately two years, he was once again brought back to the Hazleton area with a new assignment as pastor to the church of St.Mary in sleepy, little Lattimer Mines. Part of his new job was to also administer to the neighboring parish of St. Nazarius in Pardeesville. He considered music to be an excellent way in which to get to know his new parishioners and wasted no time in getting to work.

By now he already knew how much time it would take to regenerate and reap the rewards of an instrumental program. So as not waste any valuable time while the instrumental contingent was being reconstituted, he took a bold new step. Along with starting a new flutophone class, he also convened what turned out to be a group of at least 100 voices which involved members from just about every family in the parish.

Needless to say, this was not a menial undertaking. Although the instrumentalists were smaller in number and easier to handle, a group of 100 voices is something to be reckoned with. There were few places that could accommodate a group that large. This factor would become the driving force behind the Philharmonic Society’s nomadic wanderings that would not end until 1989.

Circa 1953 this massive choral group appeared for the very first time in concert. The event was held at what was then called Hazle Township High School gymnasium.

1954 marked the first appearance for the instrumental group that would ultimately become the present day Hazleton Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra. With both facets on the fast track, Ferrara began to revert back to something he had experimented with at his former assignment. While there, he had mixed his music program with a drama club and, with this combination, had produced some operettas. This experience had ignited a slow-burning flair for the theatrical that was about to burst into open flame.

In the late 1950’s, Fr. Joe, as he was affectionately called by all who knew him, laid hands on the abandoned Feeley Theatre. The showplace had won acclaim during the days of Vaudeville. As the story was told, one Vaudeville star says to the other, "If you think your good, try playin’ Hazleton!" The complex had fallen into disuse and disrepair.

Ferrara always seemed to be surrounded by throngs of very willing volunteers. With their help and a lot of elbowgrease, the Feeley was reawakened from its slumber—briefly.

Just a city block or so away sat the Capitol Theatre. It was a movie house owned by the Comerford chain. For theatrical performances, however, it was beyond compare. A deal for periodic usage was worked out and, after only a couple of annual performances, the Feeley was once again allowed to drift into peaceful sleep while the "Philharmonic Society" moved to its new home.

Just a city block or so away sat the Capitol Theatre. It was a movie house owned by the Comerford chain. For theatrical performances, however, it was beyond compare. A deal for periodic usage was worked out and, after only a couple of annual performances, the Feeley was once again allowed to drift into peaceful sleep while the "Philharmonic Society" moved to its new home.

The yearly spring extravaganzas continued and, after a while, "the concert" became a household word. In the early 1960’s movie chains were increasingly losing money and, in 1963 the Philharmonic received a devastating blow. The "Capitol" had been sold and it was going to be remodeled into storefronts. The only consolation was that the buyers allowed the Philharmonic to remove all of the staging equipment, lighting equipment, etc. that could be carried out by a given date. And so it came to pass that every flat, every backdrop, every light fixture and light bar, every cable, every cast iron counterweight—everything—was carried back to, you guessed it, the Feeley!

Week by week, piece by piece Fr. Joe and his band of youthful volunteers (with a couple of adults thrown in for good measure) refitted the Feeley with its new-used hardware and, miracle of miracles, in 1965 the Philharmonic rose out of the ashes with its 10th anniversary show. And so the tradition would continue, each show bigger and more sophisticated than the last—until 1974. In that year, a seemingly fateful blow was delivered to the Philharmonic. The Feeley complex—almost one-quarter of the block-- would be closed and razed to make way for a municipal parking lot. The annual Philharmonic extravaganzas were finally at an end.

In spiritual retrospect, God never closes a door that He doesn’t open a window somewhere else. For also during the early 1960’s, in the constant quest to grow, Ferrara executed the boldest step of all. He transformed his symphonic band into a full-fledged symphonic orchestra with the addition of the full complement of strings. What makes the venture so bold is that he developed a functional music program in which he and his volunteer staff trained the strings themselves. At its peak, the program was present in just about every parochial school in the Hazleton area. And, in one more singularly deft maneuver, he established Ferrwood Music Camp to supply a summertime complement to the school program.

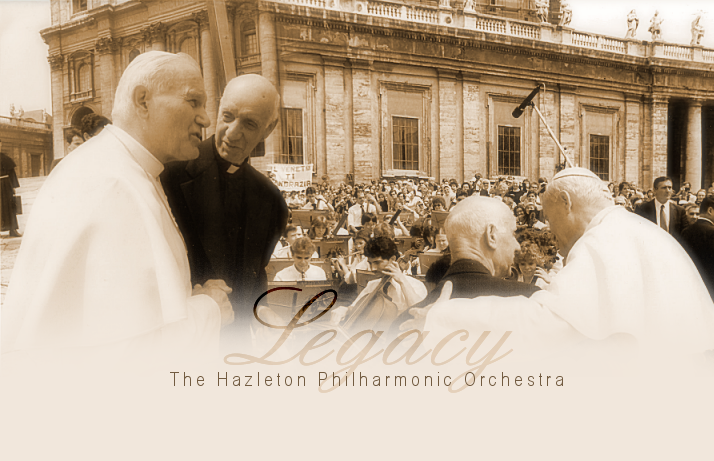

The years between 1974 and 1989 were speckled with orchestral accomplishments. In 1974 the 80-piece Philharmonic orchestra performed during a 3-week concert tour of Communist Romania. Around that same time, the orchestra journeyed to and played a concert at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. The orchestra played in many venues in and around the Hazleton area and at one point, played under the direction of Maestro Donald Voorhees, conductor of the Bell Telephone Symphony Orchestra. The orchestra’s proudest moment came in 1985 when it played a concert in St. Peter’s Square, Rome, Italy, before his Holiness Pope John Paul II during his weekly general audience.

1989 was indeed a pivotal year, for in that year the Philharmonic’s eternal search for a home of its own came to an end. April 9th of that year witnessed the dedication of the J.J. Ferrara Center for the Performing Arts.

<-- Back <--